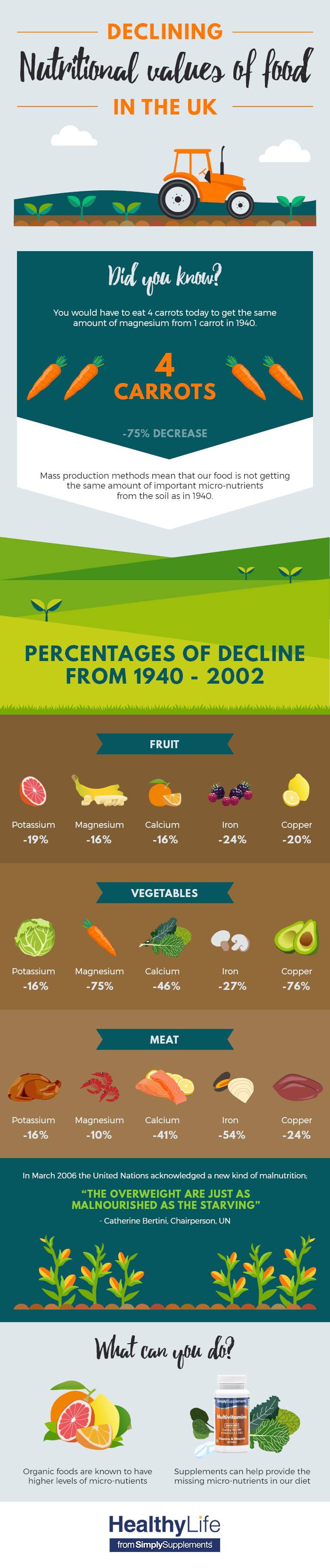

Declining Nutritional Values of Food in the UK

We can now grow food in abundance. However, while modern farming techniques help to produce bumper crops year after year, it appears that the nutritional content of our food is declining. A report comparing the nutritional content of food in 1940 and 2002 shows that the mineral content of vegetables, fruits, meat and milk has fallen significantly over the past 60 years, in some cases by as much as 70%. And the loss of essential minerals – such as calcium, magnesium and iron – from our food can have serious implications for health.

The findings have been contested by the food and farming industry, who argue that the declining numbers simply reflect changes in how minerals in food are measured. Additional changes to the way food is transported and the different varieties of food available also make direct comparisons between 1940 and 2002 tricky. However, it is unlikely that these can account for the huge difference in nutritional content. So why is the nutritional composition of our fresh food declining at such an alarming rate?

The Dilution Effect

Soil provides a range of ecosystem services and is a prime source of minerals. Traditionally, farmers used crop rotation to maintain fertile soil - leaving a field to ‘lie fallow’ for a season meant that the soil had time to recover from the effects of farming. Nowadays, the economic demands placed on farmers mean that this isn’t always viable.

Many crops are now grown for greater yield, uniform appearance, and disease resistance, and not primarily for enhanced nutritional content. The intensive farming and mass production techniques needed to produce them are depleting minerals faster than the microorganisms in the soil can replenish them. Essentially, as the yield has increased, the mineral content has decreased. This is referred to as the ‘dilution effect’. The nutritional content of a food depends on the nutrients available in the soil in which it is grown, so the key to healthier produce is healthier soil.

In addition to the dilution effect, other factors also play a role. Artificial fertilisers are also used to help crops grow quicker and bigger than before. The most commonly used fertilisers only add three important minerals to crops to help them grow - synthetic nitrogen, phosphorous and potassium. But humans need more than these three minerals for good health and wellbeing. Likewise, the increasing use of chemical pesticides reduces the uptake of minerals by plants. Food also used to be consumed close to where it was grown and didn’t have to travel far. Nowadays, many foods are picked before they are ripe to increase their storage time so they can be transported around the world.

Combined, these factors mean that over the past seventy years, the vitamin and mineral content of our food has steadily declined. The Earth Summit Report published in 1992 claimed that “there is deep concern over continuing major declines in the mineral values in farm and range soils throughout the world”. The report found that “soil depletion levels of minerals in Europe are now at 72% over the last 100 years.” And this is not just a European problem. The average mineral content of soil has fallen around the world - 76% in Asia and 85% in North America.

How Does This Affect Our Food?

Intensive farming and the use of chemical fertilisers and pesticides means that each successive generation of a crop is less nutritious than the one before and, as a result, much of the food we eat contains fewer nutrients than it did 70 years ago. For example, you would have to eat 4 carrots today to get the same amount of magnesium as from 1 carrot in 1940. Or eat 26 apples to get the same amount of iron as from 1 apple in 1940. The declining mineral content is also partly why food doesn’t taste as good as it used to.

Declining nutritional content doesn’t just apply to fruits and vegetables. The problem also exists in industrial meats and animal products. The report also examined data from 15 different meats and found that iron levels fell by an average of 47%, with the highest drop being 80%. Compared to 1940, chicken now contains more than twice as much fat, a third more calories and a third less protein. This is likely explained by the quality of animal feed.

The nutritional content of milk has also declined; iron has dropped by 60%, magnesium by 21% and calcium by 2%. Some experts have suggested that fertilisers used to speed up the growth of grass dilute the uptake of minerals. Plus, today’s cows yield five to six times as many litres per day as they used to.

What Does This Mean for Our Health?

Minerals are crucial for our physical and psychological wellbeing, and deficiencies are closely linked to serious health conditions such as osteoporosis, heart disease, liver disease, anaemia, birth defects, even cancer. So the fewer minerals we consume, the greater the risk of disease.

In March 2006, the United Nations acknowledged a new kind of malnutrition stating “The overweight are just as malnourished as the starving”. The quality of the food we consume does make a difference to our health, and as a nation, we are becoming increasingly undernourished. This concerning trend needs to be addressed to avoid serious health implications in the future.

The UK government is taking steps to combat nutrient deficiencies by introducing the mandatory fortification of certain foods, including fortifying white flour with calcium, iron and B vitamins. Animal foods are also fortified with vitamins and minerals to boost the nutritional content of meat and dairy products.

While some foods may not be as nutritious as they once were, this certainly isn’t a reason to ditch healthy foods in favour of processed, fatty alternatives. Freshly grown fruits and vegetables remain the best source of nutrients and antioxidants and still offer many health benefits. It’s just that we need to consume more than we did in the past.

How to Maintain an Optimal Nutrient Intake

Eat Your 5 a Day: Worryingly, over the past 60 years, there has been a 34% decline in UK vegetable consumption with only 13% of men and 15% of women now eating at least five portions of fruit and vegetables per day. To maintain good health, we should all eat the recommended 3 to 5 servings of vegetables plus 2 to 4 servings of fruit a day.

Take a Multivitamin: high-quality multivitamin and mineral supplements can cover any shortfalls in your diet, ensuring that you always consume sufficient levels. However, a multivitamin should never replace a healthy, balanced diet. Be sure to choose a high-quality supplement as these provide nutrients in their most bioavailable form, and so make it easier for the body to digest and absorb them.

Try Sea Sources: People in the UK eat 59% less fish than they did 60 years ago - decreasing the consumption of essential omega 3 fatty acids. But we need to be eating more, not less. Sea vegetables such as seaweed are rich in iron, while shellfish are a fantastic source of zinc. Try to eat at least two portions of seafood each week.

Go Organic: The bulky manures used to grow organic crops originate from living things and have been broken down by decomposing microorganisms. As a result, they help to improve soil quality and the nutritional content of food.

Grow Your Own: The soil in your garden or allotment is likely to be richer than over-farmed agriculture land. You may not be able to grow enough produce to cover all your needs, but the foods you do grow will likely be incredibly nutritious and superior to supermarket food.

Reduce Intake of Cereal Grains: Grains are heavily reliant on artificial fertilisers and so have a low nutritional content and are the worst offenders for degrading the soil. The three most commonly consumed grains are wheat, rice and corn, which have become staple foods around the world and are also used to fatten up livestock. Arguably, grains shouldn’t be avoided completely, but you should opt for whole grains rather than refined grains. Whole grains contain fibre, B vitamins, manganese and selenium, whereas refined grains are nutrient poor and sometimes need to be fortified with iron, folate or b vitamins to replace those lost during processing.

Sources:

http://www.mineralresourcesint.co.uk/pdf/Mineral_Depletion_of_Foods_1940_2002.pdf

http://www.un.org/en/development/devagenda/sustainable.shtml

David Thomas (2007) ‘The Mineral Depletion of Foods Available to Us as A Nation (1940–2002) – A Review of the 6th Edition of McCance and Widdowson’, Nutrition and Health, 2007, Vol. 19, pp. 21–55

Richard

Richard